Virginia Woolf has been on my “to-read” list for years and years. So it was with great pleasure that I read Orlando in the sumptuous Arion Press edition from 2005. Woolf was one of the foremost lyrical novelists of the English language. And what with her experimenting with stream-of-consciousness techniques and poking fun at literary biographers and gender roles, I found the novel very intriguing. I filled up four pages in my literary journal writing down passages that I loved and wanted to remember. I’ll try not to go overboard quoting them here. Her treatment of gender must have certainly caused a stir in the 1920’s and still seems mostly uncharted territory today. Much of it still rings true 90 years later but more on that shortly.

One theme that comes through the book is Woolf’s love of literature generally (both reading and writing) and of poetry specifically. She exposes how literature was perceived by some in society to interfere with how one is supposed to behave as a gentle(wo)man. Orlando succumbs to the “disease” of reading early on and ignores potential counterindications by starting to write as well. And writing poetry of all things. Oh no! When s/he begins to experience love that only brings the disease out of its occasional remissions:

One theme that comes through the book is Woolf’s love of literature generally (both reading and writing) and of poetry specifically. She exposes how literature was perceived by some in society to interfere with how one is supposed to behave as a gentle(wo)man. Orlando succumbs to the “disease” of reading early on and ignores potential counterindications by starting to write as well. And writing poetry of all things. Oh no! When s/he begins to experience love that only brings the disease out of its occasional remissions:

“…From love he had suffered the tortures of the damned. Now, again, he paused, and into the breach thus made, leapt Ambition, the harridan, and Poetry, the witch, and Desire of Fame, the strumpet; all joined hands and made of his heart their dancing ground.”

I love Woolf’s description of poetry as “harder to sell than prose, and though the lines were shorter took longer in the writing.” Later she further defines the writing of poetry as a “secret transaction, a voice answering a voice,” that has little to do with praise, fame, or the number of editions one’s poetry has gone through. Even while having these ideals, Orlando subsidizes any number of starving poets.

I also found her treatment of the gender theme very interesting and thoughtful. It made me realize that I haven’t seen a lot of authors tackle this subject but maybe I just haven’t run across them in my reading. The only one that comes to mind is Ursula Le Guin’s Hainish novels where people also change gender. I assume that a lot of the misunderstandings and misconceptions between the genders would go away if we spent a part of our lives as male and female. Early after her transformation from a man to a woman, Orlando is pondering her newly acquired womanhood and gives a start. The start

“…was not caused, that is to say, simply and solely by the thought of her chastity and how she could preserve it. In normal circumstances a lovely young woman alone would have thought of nothing else; the whole edifice of female government is based on that foundation stone; chastity is their jewel, their center-piece, which they run mad to protect, and die when ravished of. But if one has been a man for thirty years or so, and an Ambassador into the bargain, if one has held a Queen in one’s arms and one or two other ladies, if report be true, of less exalted rank, if one has married a Rosina Pepita, and so on, one does not perhaps give such a very great start about that.”

Woolf as the biographer and Orlando as her subject go on to ponder love and marriage, again focusing on how they are perceived differently by gender. Pulling no punches, she writes:

“… love—as the male novelists define it—and who, after all, speak with greater authority?—has nothing whatever to do with kindness, fidelity, generosity, or poetry. Love is slipping off one’s petticoat and—But we all know what love is.”

Later Orlando, feeling restless and not quite herself, not being able to write and unable to shake the mood “was forced at length to consider the most desperate of remedies, which was to yield completely and submissively to the spirit of the age, and take a husband.” After which, happy as she is, she still can’t help but wonder about the institution. She ponders while her husband is off sailing around Cape Horn:

“She was married, true; but if one’s husband was always sailing round Cape Horn, was it marriage? If one liked him, was it marriage? If one liked other people, was it marriage? And finally, if one still wished, more than anything in the whole world, to write poetry, was it marriage? She had her doubts.”

It will take another read and some thinking of my own to decide where I agree or disagree with her take on poetry, love, marriage, and men and women. But it’s wonderful that a book written 90 years ago can still bring up valid questions and cause one to search within for one’s own answers.

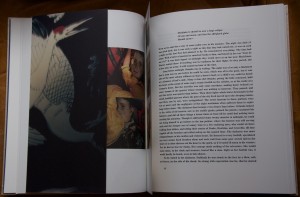

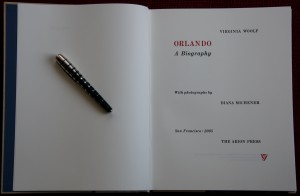

And what about the book itself? How has the Arion Press edition enhanced (or hindered) the reading of the novel? Does it provide a “whole book experience”? In short, it was wonderful. The book is a bit too large (large quarto, 13 by 10 inches) to make for comfortable reading just anywhere. As long as I was safe in one of my favorite reading chairs or in bed it was no problem. The paper is Mohawk Superfine and shows off the Century Bold type well. An interesting result of this particular choice of type was that I was equally comfortable reading the book with or without my glasses. I don’t think I’ve ever experienced that before.

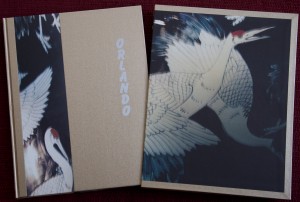

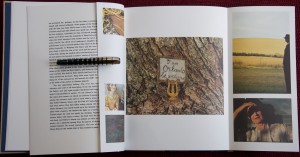

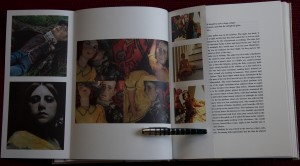

I found the illustrations very apropos for the text. I think Diana Michener came up with a concept for the photographs that worked very well with the story. The photographs are interestingly contained within folded panels that show the recurring images of the Chinese Crane vase on the outside with the photographs being revealed inside when one opens the panels. One feature that I really liked was the inclusion of an “Artist’s Note” before the colophon. This gives some insights into Michener’s process in coming up with the illustrations. I love having this kind of information on evolution of a book’s design.

The book is bound with gold cloth and paper panels printed with a Chinese vase design and comes with a matching slipcase. The title is stamped on the gold cloth covering the spine and the front cover of the book and on the spine of the slipcase. Personally, I always like a slipcase or some other protective cover on high-end books like these. I especially like slipcases that have the title printed on the spine so they can be shelved with the book spine inward to protect them and you can still identify the book without pulling from the shelf. I’ve seen too many older books with faded spines and would much rather have a faded slipcase. I’m blessed to live in a climate where I don’t have to worry about humidity or vermin but dust is always an issue and it’s nice to just have to worry about the top of the slipcase instead of the bookblock.

As a printer and publisher herself with the Hogarth Press, I hope Woolf would be pleased with the Arion Press’ treatment of her unique novel.

Availability: Orlando is limited to an edition of 400 copies and was still available from the Arion Press as of the date of this post. If you are ever in San Francisco, check out the Press. Their gallery is open daily and has several of their books displayed, including this one last time I was there.