I had the luck to visit with Griffin at his No Reply press when passing through Portland in the early fall. We have been collaborating on this interview for the last few months and I was hoping to get some photos of the press to support it while there. We got so engrossed in talking and in drinking tea in the press room that I got almost no photos. Oh well. I love my camera but I don’t like to miss too much life while behind the lens.

I broke the interview into two parts for readability and because I just couldn’t edit it down. Too much good stuff. Here is Part I:

Books and reading have been part of my life as long as I can remember. While I don’t have memories of being read to, I have vivid memories of the children’s books we had in our house. I still have a copy of a letter I wrote to my grandmother stating I had “started my library,” meaning I had a new desk with shelves above it that I was beginning to fill with books. As an auto-didact, books are my primary tool for learning.

How and when did you come to books? Was it as a reader (book as text) or as a craftsperson or artist (book as object)? And how does that influence your choice of what to publish?

My parents are both readers. In fact, my dad is an English teacher. In my case, I’m afraid the dots aren’t hard to connect.

I was a late reader. The first novel I read on my own was called Al Capone Does My Shirts. It’s about the kid of an Alcatraz guard who passes notes to Al Capone through the laundry, since the prisoners do the laundry service. It was a good book! Then I read all of Markus Zusak’s novels. (Naturally, it was a thrill to get to know him later on as a collaborator.) That sort of set the template for my reading. I’m a deep-diver. Last year I read or reread all of Vladimir Nabokov’s novels written in English. I have just embarked upon another target, Samuel Beckett. My friend Christopher Ricks has exhumed some previously unpublished material of his, so before we (and if we) pursue its publication, I’ll need to read at least a representative sample of Beckett’s work with a good helping of critical commentary and biography. I have great depth with some writers but none whatsoever with others. For example, I’ve never read anything by John Steinbeck, Mark Twain, or Gabriel García Márquez. On the other hand, I’ve read everything published by T. S. Eliot, Jane Austen, Vladimir Nabokov, Robert Caro, Toni Morrison, William Blake, Jorge Luis Borges, and I’m getting close with Willa Cather. So, reading-wise, I’m a bit like my lawn: Wonderfully verdant in spots and barren in others.

A grave admission for a private press proprietor, but reading isn’t an everyday part of my life anymore. I’m either reading – and it’s the central aspect of my life – or I’m not. As a student, I was reading. I read all seventy volumes of The Harvard Classics, and most of Nabokov, and all of Borges, and most of Hugo and Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, and on and on, and I read enough to grow quixotic opinions, preferring Marlowe to Shakespeare and Thackeray to Dickens. I read the Bible and the Quran and Aśvaghoṣa and Lucian and Cicero and Bashō and a lot of Agatha Christie murders. So far this year, 2023, I’ve managed to read 246 pages of Robert Graves’ I Claudius and that’s it. But I’m loving it! The problem, for me, is that I’m a bit of a workaholic, so when literature is your work it’s difficult to relax and simply enjoy reading. You keep thinking: “Huh, that passage would make a good broadside – better run down to the workshop and see if I have enough Zerkall offcuts to make it happen!” These days, my greatest joy is reading manuscripts and materials yet-to-be-published. I receive manuscripts all the time. It’s wonderful to read something in its infancy, before the rest of the world has seen it.

In general, also, I’m a glacially slow reader. I take my time. Highlight. Make notes. Stop mid-chapter and go to the Hotcake House for a burger and then a walk. When you finally visit me, J, pull any book off my shelf. There’s no mistaking a book I’ve read with a book I haven’t. If I’ve read it, it’s covered in scrawl, probably wavy from the shower, smells like booze, endless dog ears, junk falling out from between the pages. Physical books and the literature they contain converge in my memory. When I think, “Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame,” the image that comes to mind for me isn’t the hunchback or the gothic spires or Esmeralda dancing with her goat, but my Notre-Dame. I know exactly what it looks like, where it is.

So, my pursuit of private presswork is first a means of honoring literature and secondarily as a means of partaking in a wonderful craft tradition. I would take no pleasure, for example, in printing letterpress wedding invitations or hand-binding journals. My heart wouldn’t be in it; it’d be a chore.

That isn’t to say the craft is incidental for me. Making things is what makes me happiest, beside being inside a good book. I built No Reply’s current workshop myself, hammer and nail. I do much of my own plumbing, I’m my own electrician. Last week I built a patio. I’m a big materials guy. My favorite paper is Hahnemühle Biblio. My favorite wood is Douglas Fir. My favorite gravel is dry ⅝-minus. My favorite motor oil is SAE-30, and my favorite solvent is Mineral Spirits. I make many of No Reply’s decorative papers myself, increasingly with novel or experimental methods. I like it when something is sui generis. No book in the world will have cover papers quite like my upcoming The Last Question; no patio in the world is quite like mine. For better and worse!

As to the choice of what to publish, each edition comes about differently and organically. Like most ideas, they start so small that you can’t remember exactly when or where or why they started. They just happen. I had a good education in digital typesetting and layout while at Thornwillow Press, so I often play around with an idea typographically just to see if it clicks. It’s gotta click! And sometimes, the materials drive the choice of literature. Earlier this year, I accidentally ordered (don’t ask) some really odd fuschia papers from St. Armand – something between “sasquatch valentine” and “auntie’s ugly sweater”. Can’t figure out what to do with them. They’ll make terrific wrappers for a small booklet. So, I laid out a dozen different ideas – Emily Dickinson poems, a showing of the woodblocks of Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita, the Four Quls of the Quran, Blake’s Augeries of Innocence, poems by my brother’s partner Imani, an essay I’ve long admired about secondary win conditions in the board game Diplomacy, a sweeping scene from Death Comes for the Archbishop, my own essay of appreciation for Nabokov’s Bend Sinister, some poems by a private press colleague. I did fifteen minute layouts for all of these ideas, to see if anything clicked. No clicks, sadly. So the fuschia paper remains, unused, until a fitting idea comes along.

How have you changed over the course of time? Do you presently consider yourself more of a reader or collector when it comes to private press books?

I’m in the minority here. I appreciate private press books first and foremost as art objects. Functionally, hand- or fine-bookmaking is long obsolete. It isn’t necessary for the conveyance of literature; it has passed into the realm of art and craft. So, that’s how I appreciate it. I do read from my collection, but I’m often distracted from the literature by the art object. Ultimately, I don’t think the reading experience itself is leaps and bounds beyond a well-designed trade book. In fact, I’m glad it isn’t. It would be a little tragic, after all, if the difference between a captivating reading experience and a mediocre one were the cost of the book in your hands. W. A. Dwiggins – the typographer and book designer I admire most – was actually opposed to the fine press movement in many respects. He thought that good design and good bookmaking shouldn’t be the realm of artisans and collectors, but everyday trade practice. Ultimately, if you’re wrapped up in what you’re reading, the medium melts away.

Now, what private presswork can do, and what ultimately I think it should do, is honor literature. We do things by hand when we needn’t on special occasions, or out of respect, or in reverence, or to honor our subject. Everybody knows a home-made birthday cake is more special than a store-bought one, regardless of how it tastes. Harry digs Dobby’s grave by hand when he could easily have used magic. Handiwork is a matter of respect.

There is certainly a continuum of collectors. Some only collect books they intend to read and know a priori that they will enjoy, having read the literature before. Others only collect books which employ unique materials or advanced bookbinding techniques. This community is incredibly diverse for its small size. There is also a continuum among proprietors. One private press proprietor might tell you that their purpose is to make beautiful editions of cherished literature. Another might tell you that their purpose is to publish new literature. Another might tell you that literature is secondary, and that for them bookmaking is an art (i.e. a matter of self-expression). I’d consider myself an Option D “All of the Above” sort of person.

I believe we “met” in the Fine Press Forum on LibraryThing when you were doing some work for Thornwillow Press.

Can you expand on your experience and history in publishing that has culminated in being the proprietor of a private press?

Your Fine Press Forum! It’s a wonderful community you’ve started there.

My favorite saying of Sufi: “Different roads lead to the same place”. That certainly applies to me here. My path to private presswork was convoluted, and really a convergence of several paths. It’s great how the smallest chance things can grab the wheel of your life.

I grew up doing projects at the Independent Publishing Resource Center in Portland, an incredible collective of artists and writers and craftspeople who have built a community space for self-publishing of all sorts. Everything from zines to broadsides, screenprinting to letterpress, fine gallery artwork to paper snowflake cutouts. So, I had some latent interest in bookmaking when David Eckel, the scholar of Mahayana Buddhism, gave me a copy of the Club of Odd Volumes’ Catullus. Printed letterpress by Bradley Hutchinson, designed by Jerry Kelly – a real gem. That was the beginning of my fine press collection. But this Catullus was the second edition of the translation, the first having been published by Thornwillow Press. Thornwillow Press: I remembered the name. A year later, while on an academic fellowship to study the unpublished manuscript materials of a disgraced Victorian Poet, William Cory née Johnson, I met Luke Pontifell and we hit it off.

In 2016, Thornwillow had reached a crossroads. The company had gone through several eras, and was in the twilight of its latest, as a stationer to several global luxury brands – particularly Cartier and Montblanc – and as the White House’s nearly-official bookmaker. Luke had begun crafting an output with an eye toward mass appeal. He didn’t want the press to rely, as it had, on the contracts of a few big brands. In particular, he had begun printing broadsides, chapbooks, and multi-state larger editions. My working background was in crowdfunding, and I thought these smaller publications would be a good fit for it. Savine jumped on the idea: “Do it!” We decided to give it a try with Thornwillow’s broadsides. We filmed a short introduction. (I’m the guy off-camera, coaching Luke on how to say “Hi”.) We shot some photos in the Pontifell’s house. We wrote some advertising copy. That was that!

The first Kickstarter campaign dramatically beat our expectations, and that set the template for thirty more. I increasingly took part in the editorial and design side of things as well – culminating, I think, in Thornwillow’s Genesis, which is a landmark edition in the publication history of Biblical texts. I designed the layout in collaboration with Luke for Sherlock Holmes Hexalogy, Frankenstein, The Waste Land, Beauty is the Beginning of Terror, Pride & Prejudice, The Great Gatsby, Portrait of a Free Man, and Genesis. I moved to Newburgh for a year, and basically lived with the Pontifells in the cottage next to their house. I’m really proud of my work at Thornwillow, and can’t recommend the press enough. Luke and Savine are wonderful, and probably the hardest working people I know. Their thirty-year partnership is an inspiration, and they’ll undoubtedly be remembered as among the most important figures in the history of the fine press movement.

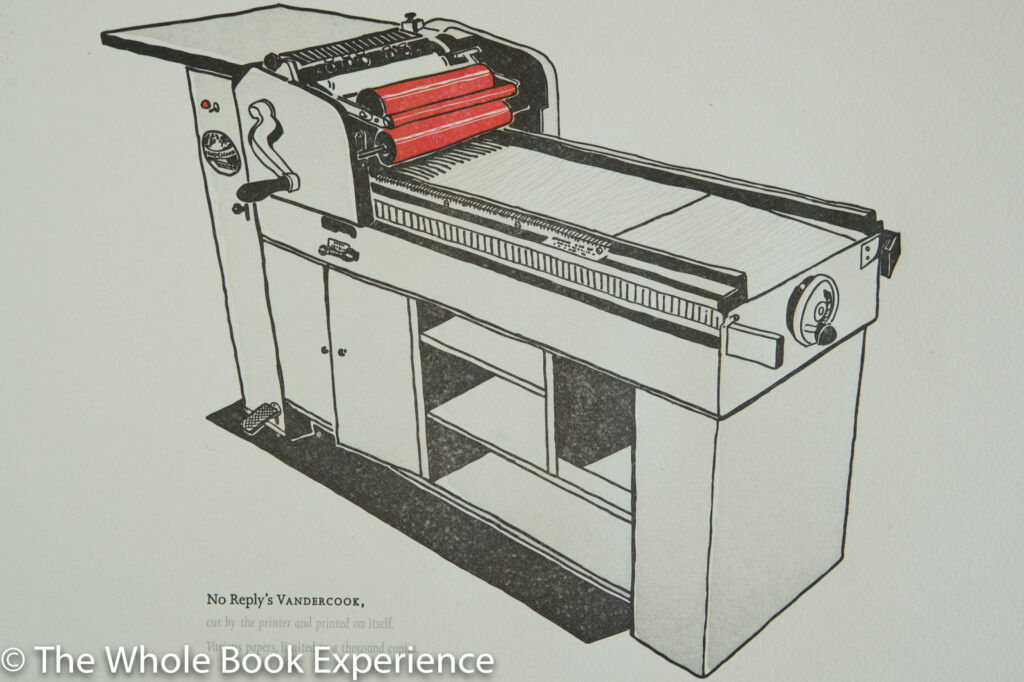

While at Thornwillow, I had the opportunity to learn letterpress printing on Luke’s Vandercook Universal I – the same he had used to print Thonwillow’s earliest editions. I don’t know why – perhaps laziness – but rather than seek out a worthier manuscript for my first private press edition, I grabbed some poems that I had written in high school emulating William Blake’s style. I set the type on a kitchen table in 10 point Jenson cast by Patrick Reagh; I used offcuts from Thornwillow’s first Seven Towers volume. I remember – though I don’t remember why – using the top of my porcelain toilet’s tank as a work surface for sewing the books. It was a ragtag production, and No Reply’s first.

After about four years with Thornwillow, it was time for me to move on. I’d saved up enough money to afford some frugal adventuring, so I left New York, traveled, dyed my hair blue, danced a lot, met my amore, and lived off the free coffee and snacks they have at stodgy European social clubs where you can sort of just walk in if you’re wearing a suit (even with blue hair!). “Pardon, pardon: je suis Américain! Je ne parle pas Francais. Où sont les snacks?” Importantly, I started dabbling with bookmaking as a steady hobby. The first few No Reply editions were conceived all over the place in Europe – an apartment in Paris, another in Brussels, materials salvaged from the back of a legatoria in Venice. Nothing much came of them. I considered pursuing bookmaking more seriously in Europe, but it just wasn’t possible. Don’t get me wrong, there are wonderful craft traditions in Europe, but they are indeed traditions, and therefore often entropic. When a century-old bookbindery closes, a new one doesn’t usually open. The fees and paperwork involved in starting even the smallest business are pretty headspinning, and if you do succeed, the tax rates make it difficult to grow. When you’re paying twelve percent in Oregon, a high tax state, you’re paying fifty percent in Belgium. Even small things – like the U. S. Postal Service’s “Media Mail” rate – made bookmaking wildly more feasible stateside, so I decided to move back, if only for a few months, to make a serious attempt at it.

Home again home again jiggety-jig. My home is Portland. Portland is a craft town. There’s nothing quaint about it, nothing done for the tourists, nothing done “to keep the tradition alive”. It’s industrial, it’s everyday. In my lifetime, most of the Starbuckses and cineplexes in inner-Southeast have closed down, unable to compete with craft roasters and local theaters. Within a five minute walk of my house there’s a bindery, a magnesium platemaker, an engraver, a wood shop, a ceramics shop, several breweries and coffee roasters. All this sometimes gets derided as “hipster,” but it’s really just decent small business. The only chains we have in my neighborhood are a Subway Sandwich and a Post Office. I honestly believe there’s no better place in the world to run a craft business or a small business of any kind. Starting No Reply in earnest only took a fifty dollar business registration fee and a few handshake agreements with some neighbors. That’s it.

Jenn Lawrence, who has a beautiful letterpress studio – killer machines, sky high ceilings, that smell – agreed to print The Masque of the Red Death. (One of No Reply’s fun facts is that some of our books are signed by Jennifer Lawrence – but not that one!) A few neighborhoods over, I rented a small studio in a gorgeous art deco building for two hundred bucks a month, and set up a popup hand-bindery. I borrowed some tools and materials from the Independent Publishers Resource Center, and launched the edition on Kickstarter.

The Masque of the Red Death is the story, of course, of a pandemic. Somebody shows up to a party, takes off their mask, and everybody dies. And I announced it in January 2020. The timing was a ridiculous accident and the edition really took off. Red Death sold out and interest grew for my past homespun editions.

I had never planned for No Reply to become my primary employment, but the pandemic put a halt to my life as it had been, and landed me back in Portland for the foreseeable future. With little else to do, I poured myself into No Reply. Since the start of the pandemic, I’ve acquired a few presses, built out my own bindery, collected wonderful papers from across the globe, taught myself a few of the related crafts. I’m excited about the presswork going forward, because everything is finally in place. In the past it was always a ragtag operation. Now, I have everything I need at my fingertips. That’ll empower me to be more ambitious, sure, but also simply bring the finished books closer to my vision for them. But I’m still quite new at this, and very much at the back of the pack when it comes to the private presses that are out there, so take everything I say with a scoop of salt.

Your description of what makes a press a private press on your website is wonderful. It’s the definition I use to differentiate between private and fine presses, and of course from trade or commodity presses. It also smacks of the way I use the word “provenance” in my tea business. I think I latched onto that word from the antique business as described in ??’s book, The Goldfinch. It’s the history and life experience of the item: who made it, did the maker receive fair compensation for their work/art, where it and it’s components came from, whose hands has it passed through and why, has it been loved or abused, etc. There is a big difference in drinking tea out of a commodity manufactured teacup and my beloved nana’s cup. There is a huge difference in reading a tattered Oxford paperback edition of Shakespeare’s Pericles compared to reading the incredible Barbarian Press edition. Obviously it plays into value as well, as in the case of a Limited Editions Club copy of Ulysses signed by Joyce and Matisse versus a copy that is not.

Do you have any thoughts on this concept of “provenance” with respect to books and how that inspires your work at No Reply?

To address the first point first: Everybody has their own definitions of these things, which I think is wonderful. When you have a community as small and as open as ours, there can be genuine and good faith disagreement about the boundaries of what constitutes a fine press or a private press. The “least common denominator” definition, more or less, is that fine press means “exceptionally well-made” and private press means “even better, and probably handmade to boot.” I think these definitions are pretty milquetoast, because they add no real description. Why say, “This is a fine press book,” when you could simply say, “This is an exceptionally well-made book?”

I am of the opinion that the term “fine press” should be reserved as a matter of historical lineage, and “private press” as a matter of operation.

The fine press movement was a reaction against the industrialization of bookmaking and publishing more generally. It was inherently anti-commercial, focusing on quality of craft and design when the market was moving in the other direction. Whatever remains in that spirit, in whatever context, is fine press. The bookshelves in my living room are split in half – on the left, fine press, on the right, trade books. The thing is, many of the trade books were made in basically the same way as many of the fine press books. My Arion Press edition of Miller’s The Price: monotype letterpress printed on heavy paper with a Smyth-sewn full-cloth cased binding. My Doubleday first edition of Nabokov’s Pnin: monotype letterpress printed on heavy paper with a Smyth-sewn full-cloth cased binding. The difference is entirely contextual. The Doubleday edition was made when these processes were the norm; the Arion edition was made when these processes were largely extinct.

“Private press” has a simpler definition. Every book has a publisher (responsible for its content) and a bookmaker (responsible for its manufacture). In a private press, that person or small group of persons is one and the same. To put it in Marxist terms, labor and capital are one.

I think many would disagree with my definitions simply because they are capacious. They admit a lot of “whatabouts”. Still, they offer descriptive information beyond “these are really nice books,” so they’re how I personally use the terms.

To your actual question: Provenance. Typically you hear the word in art collecting because provenance is required to establish the credibility of an attestation to a particular artist. This painting is by Monet because we have a receipt of Monet selling it to Paul, and Paul selling it to John, and John selling it to George, and George selling it to Ringo, and Ringo gave it to Griffin who was a dummy and hung it over his new patio where the rain and raccoons got to it. The lineage of a thing, for better and worse. When you practice a centuries-old craft, everything around you has a story. Take, for example, my Vandercook Universal I – No Reply’s primary press. It was manufactured in Chicago and then shipped originally to Los Angeles, where it served as a galley proofing press for the Los Angeles Times. (In the fifties and sixties – you can imagine what stories it broke!) Then it was sold to Mercury Press in San Francisco, an active part of the California printing renaissance. Then, later, to Serenity Press in Ashland, Oregon. For twenty years it printed primarily poetry broadsides – including original poetry by no fewer than four U. S. Poet Laureates. And then, finally, it came to me in Portland. Basically, this Vandercook has been making a seventy year journey up I-5. When I’m done with private presswork, it’d only be fitting for me to sell it to somebody in Seattle or Vancouver to complete its West Coast tour.

It’s important to me to know the provenance of everything that goes into the books. Down to the furniture. The coat rack in my workshop is actually a hat rack that stood for four decades in the law office of a lawyer who the Rajneeshees tried to assassinate. My light table was owned and used by the McMenamin Brothers’ head typographer. My 1889 Challenge stack cutter is from the shop of Mr. Ken Bortvedt, local stationer, who turns 97 next month. The walls are old growth Doug Fir (bark still attached in places). Tons of Oregon history in such a small space. I think these books are really alive, and at the risk of sounding a bit cornball, their spirit is quite important to me.

Note: the device used to mark each of Griffin’s responses is a representation of the Portland neighborhood where he grew up, had his first workshop, and still lives close to. Pull up a map of Portland downtown along the river and it’ll be obvious.

Wow, this guy is long-winded! 🥱 😉

While we wait for your beautiful books, we have plenty of time to hear what makes your press so special!