“So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation, which, in the face of civilization, artificially creates hells on earth, and complicates a destiny that is divine with human fatality; so long as the three problems of the age—the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of women by starvation, and the dwarfing of childhood by physical and spiritual night—are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words, and from a yet more extended point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, books like this cannot be useless.” –Preface

“So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation, which, in the face of civilization, artificially creates hells on earth, and complicates a destiny that is divine with human fatality; so long as the three problems of the age—the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of women by starvation, and the dwarfing of childhood by physical and spiritual night—are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words, and from a yet more extended point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, books like this cannot be useless.” –Preface

Thus Hugo prefaced his mighty novel when Les Misérables was published in 1862. While there have been spots of daylight in the 150 years since then, it is sad to say that in many ways things have not changed much. If they had, maybe Hugo would be alright with the fact that many people only know Les Misérables as the dumbed-downed Disneyfied musical version that concentrates on the love story of Cosette and Marius and mostly ignores the social issues that take up much of the novel. But I suspect he would be horrified because books like Les Misérables are still very much needed. You need only look at the trend in our country to disenfranchise felons, people of color, and the poor to know that Les Misérables is still required reading for those concerned with social justice.

Thus Hugo prefaced his mighty novel when Les Misérables was published in 1862. While there have been spots of daylight in the 150 years since then, it is sad to say that in many ways things have not changed much. If they had, maybe Hugo would be alright with the fact that many people only know Les Misérables as the dumbed-downed Disneyfied musical version that concentrates on the love story of Cosette and Marius and mostly ignores the social issues that take up much of the novel. But I suspect he would be horrified because books like Les Misérables are still very much needed. You need only look at the trend in our country to disenfranchise felons, people of color, and the poor to know that Les Misérables is still required reading for those concerned with social justice.

Much is made of Hugo’s digressions into various topics as the tale of Jean Valjean unfolds. From those digressions have sprung many abridgements. Some translators, such as Norman Denny, move whole sections to appendices. The section I always heard the most complaints about concerns the description of Napolean’s defeat at Waterloo. I actually found that section quite interesting. The diversions into the Paris sewers and about the gamins of Paris also dovetailed well enough into the story line to not be too troubling. I had a harder time with the digression into the subject of the cloister that is prompted by Jean and Cosette’s arrival at Petit Picpus. The hardest thing for me was really just trying to understand the timeline of French history between the monarchs, the emperor, the revolutions and revolts, and other events given short shift in my previous studies of United States-centric history.

Much is made of Hugo’s digressions into various topics as the tale of Jean Valjean unfolds. From those digressions have sprung many abridgements. Some translators, such as Norman Denny, move whole sections to appendices. The section I always heard the most complaints about concerns the description of Napolean’s defeat at Waterloo. I actually found that section quite interesting. The diversions into the Paris sewers and about the gamins of Paris also dovetailed well enough into the story line to not be too troubling. I had a harder time with the digression into the subject of the cloister that is prompted by Jean and Cosette’s arrival at Petit Picpus. The hardest thing for me was really just trying to understand the timeline of French history between the monarchs, the emperor, the revolutions and revolts, and other events given short shift in my previous studies of United States-centric history.

One of the places where Hugo falls down for me, and it is partially due to the time in which he is writing, is in his development of female characters. This despite his stated goal of highlighting the degradation of women by the crushing weight of poverty, misery, and men. But even with that lack of developed depth in their characters, I couldn’t help but feel sorrow for Fantine, sympathy for the lovelorn Eponine, and hope for Cosette. I lost patience entirely with Cosette towards the end as she basically let Jean die of a broken heart.

One of the places where Hugo falls down for me, and it is partially due to the time in which he is writing, is in his development of female characters. This despite his stated goal of highlighting the degradation of women by the crushing weight of poverty, misery, and men. But even with that lack of developed depth in their characters, I couldn’t help but feel sorrow for Fantine, sympathy for the lovelorn Eponine, and hope for Cosette. I lost patience entirely with Cosette towards the end as she basically let Jean die of a broken heart.

Where Hugo shines is in his eloquent descriptions of the joys and tragedies of humanity and human existence. Even if I’m champing at the bit for the story line to move along, I always enjoy his humanistic philosophies, and am much more amenable to them than a description of a historical event. Like all of his major works, he writes on many themes. On that greatest of all human needs, love, he writes some wonderful passages:

Where Hugo shines is in his eloquent descriptions of the joys and tragedies of humanity and human existence. Even if I’m champing at the bit for the story line to move along, I always enjoy his humanistic philosophies, and am much more amenable to them than a description of a historical event. Like all of his major works, he writes on many themes. On that greatest of all human needs, love, he writes some wonderful passages:

Let us say parenthetically that to be blind and to be loved is one of the most strangely exquisite forms of happiness upon this earth, where nothing is perfect. To have continually at your side a wife, a sister, a daughter, a charming being, who is there because you have need of her, and because she cannot do without you; to know yourself indispensable to a woman who is necessary to you; to be able constantly to gauge her affection by the amount of her presence which she gives you, and to say to yourself: “She devotes all her time to me because I possess her entire heart”; to see her thoughts in default of her face; to prove the fidelity of a being in the eclipse of the world; to catch the rustling of a dress like the sound of wings; to hear her come and go, leave the room, return, talk, sing, and then to dream that you are the center of those steps, those words, those songs; to manifest at every moment your own

Let us say parenthetically that to be blind and to be loved is one of the most strangely exquisite forms of happiness upon this earth, where nothing is perfect. To have continually at your side a wife, a sister, a daughter, a charming being, who is there because you have need of her, and because she cannot do without you; to know yourself indispensable to a woman who is necessary to you; to be able constantly to gauge her affection by the amount of her presence which she gives you, and to say to yourself: “She devotes all her time to me because I possess her entire heart”; to see her thoughts in default of her face; to prove the fidelity of a being in the eclipse of the world; to catch the rustling of a dress like the sound of wings; to hear her come and go, leave the room, return, talk, sing, and then to dream that you are the center of those steps, those words, those songs; to manifest at every moment your own  attraction, and feel yourself powerful in proportion to your weakness; to become, in darkness and through darkness, the planet round which this angel gravitates—but few felicities equal this. The supreme happiness of life is the conviction of being loved for yourself, or, more correctly speaking, loved in spite of yourself; and this conviction the blind man has. In this distress, to be served is to be caressed. Does he want for anything? No. When you possess love, you have not lost the light. And what a love! A love entirely made of virtues. There is no blindness where there is certainty; the groping soul seeks a soul and finds it, and this fond and tried soul is a woman. A hand supports you,–it is hers; a mouth touches your forehead,–it is hers; you hear a breathing close to you,–it is she. –I, p. 164

attraction, and feel yourself powerful in proportion to your weakness; to become, in darkness and through darkness, the planet round which this angel gravitates—but few felicities equal this. The supreme happiness of life is the conviction of being loved for yourself, or, more correctly speaking, loved in spite of yourself; and this conviction the blind man has. In this distress, to be served is to be caressed. Does he want for anything? No. When you possess love, you have not lost the light. And what a love! A love entirely made of virtues. There is no blindness where there is certainty; the groping soul seeks a soul and finds it, and this fond and tried soul is a woman. A hand supports you,–it is hers; a mouth touches your forehead,–it is hers; you hear a breathing close to you,–it is she. –I, p. 164

There are fathers who do not love their children; but there is not a grandfather who does not adore his grandson. III, p. 118

There are fathers who do not love their children; but there is not a grandfather who does not adore his grandson. III, p. 118

You gaze at a star for two motives, because it is luminous and because it is impenetrable. You have by your side a sweeter radiance and greater mystery—woman. IV, p. 116

Do you what you will, you cannot destroy that eternal relic of man’s heart, love. –IV, p. 175

…When two mouths, which have become sacred by love, approach each other in order to create, it is impossible but that there is a tremor in the immense mystery of the stars above this ineffable kiss.

…When two mouths, which have become sacred by love, approach each other in order to create, it is impossible but that there is a tremor in the immense mystery of the stars above this ineffable kiss.

These felicities are the real ones, thee is no joy beyond their joys, love is the sole ecstasy, and all the rest weeps.

To love or to have loved is sufficient; ask nothing more after that. There is no other pearl to be found in the dark folds of life, for love is a consummation. –V, p. 208

In certain supreme conjunctures has it not happened to all of us, that after asking a question we have stopped our ears, in order not to hear the answer? A man is especially guilty of such an act of cowardice when he is in love. –V, p. 237

In certain supreme conjunctures has it not happened to all of us, that after asking a question we have stopped our ears, in order not to hear the answer? A man is especially guilty of such an act of cowardice when he is in love. –V, p. 237

He is also direct in his writing about the institution of religion:

The holy law of Christ governs our civilization, but does not yet penetrate it. Slavery is said to have disappeared from the civilization of Europe. It has not; it still exists, but it weighs down woman alone, and is called prostitution. It weighs down woman, that is to say, grace, weakness, beauty, motherhood. This is not one of the least disgraces of man.

–I, p.183

God imparts to men His will visible in events, an obscure text written in a mysterious language. Men at once make themselves translations of it, hasty, incorrect translations, full of errors, gaps and misunderstandings. Very few minds comprehend the divine language; the more sagacious, the calmer, and the more profound decipher slowly, and when they arrive with their version the work has been done long before; there are already twenty translations offered for sale. From each translation springs a party, and from each misunderstanding a failure, and each party believes that it has the only true text, and each faction believes that it possesses the light. –IV, p. 18

God imparts to men His will visible in events, an obscure text written in a mysterious language. Men at once make themselves translations of it, hasty, incorrect translations, full of errors, gaps and misunderstandings. Very few minds comprehend the divine language; the more sagacious, the calmer, and the more profound decipher slowly, and when they arrive with their version the work has been done long before; there are already twenty translations offered for sale. From each translation springs a party, and from each misunderstanding a failure, and each party believes that it has the only true text, and each faction believes that it possesses the light. –IV, p. 18

And the military-industrial complex and the business of war:

It has been calculate that in salvos, royal and military politeness, exchanges of courtesy signals, formalities of roads and citadels, sunrise and sunset saluted every day by all the fortresses and vessels of war, opening and closing gates, etc., the civilized world fired every twenty-four hours, and in all parts of the globe, one hundred and fifty thousand useless rounds. At six francs the round, this makes 900,00 francs a day. Three hundred millions a year expended in smoke. During this time poor people are dying of starvation. –II, p. 68

…armed peace, that ruinous expedient of civilization suspecting itself. —IV, p. 19

And, of course theme for which the novel gets its name, that scourge of human society, poverty:

Life became severe for Marius; eating his clothes and his watch was nothing, but he also went through that indescribable course which is called “chewing the cud.” This is a horrible thing which contains days without bread, nights without sleep, evenings without candle, a house without fire, weeks without work, a future without hope, a threadbare coat, an old hat at which the girls laugh, the door which you find locked at night because you have not paid your rent, the insolence of the porter and the eating-house keeper, the grins of neighbors, humiliations, dignity tramped under foot, any work taken, disgust, bitterness, and desperation. Marius leaned how all this is devoured, and how it is often the only thing which a man has to eat. At that moment of life when a man requires pride because he requires love, he felt himself derided because he was meanly dressed, and ridiculous because he was poor. At the age when youth swells the heart with an imperial pride, he looked down more than once at his worn-out boots, and knew the unjust shame and the burning blushes of wretchedness. It is an admirable and terrible trial, from which the weak come forth infamous and the strong sublime. It is the crucible into which destiny throws a man whenever it wishes to have a scoundrel or a demi-god. –III, p. 113

Life became severe for Marius; eating his clothes and his watch was nothing, but he also went through that indescribable course which is called “chewing the cud.” This is a horrible thing which contains days without bread, nights without sleep, evenings without candle, a house without fire, weeks without work, a future without hope, a threadbare coat, an old hat at which the girls laugh, the door which you find locked at night because you have not paid your rent, the insolence of the porter and the eating-house keeper, the grins of neighbors, humiliations, dignity tramped under foot, any work taken, disgust, bitterness, and desperation. Marius leaned how all this is devoured, and how it is often the only thing which a man has to eat. At that moment of life when a man requires pride because he requires love, he felt himself derided because he was meanly dressed, and ridiculous because he was poor. At the age when youth swells the heart with an imperial pride, he looked down more than once at his worn-out boots, and knew the unjust shame and the burning blushes of wretchedness. It is an admirable and terrible trial, from which the weak come forth infamous and the strong sublime. It is the crucible into which destiny throws a man whenever it wishes to have a scoundrel or a demi-god. –III, p. 113

…he who has only seen man’s misery has seen nothing, he must see woman’s misery; while he who has seen woman’s misery has seen nothing, for he must see the misery of the child. III, p. 183

…he who has only seen man’s misery has seen nothing, he must see woman’s misery; while he who has seen woman’s misery has seen nothing, for he must see the misery of the child. III, p. 183

In all these torments, and for a long time, he had discontinued his work, and nothing is more dangerous than discontinued work, for it is a habit which a man loses—a habit easily to give up, but difficult to re-acquire. –IV, p. 41

They doubtless seemed very depraved, very corrupt, very vile, and indeed very odious; but persons who fall without being degraded are rare; besides, there is a stage where the unfortunate and the infamous are mingled and confounded in one word, a fatal word, Les Misérables; and with whom lies the fault? And then, again, should not the charity be the greater the deeper the fall is? III, p. 184

They doubtless seemed very depraved, very corrupt, very vile, and indeed very odious; but persons who fall without being degraded are rare; besides, there is a stage where the unfortunate and the infamous are mingled and confounded in one word, a fatal word, Les Misérables; and with whom lies the fault? And then, again, should not the charity be the greater the deeper the fall is? III, p. 184

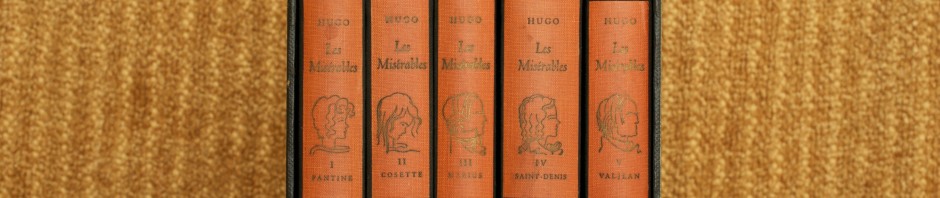

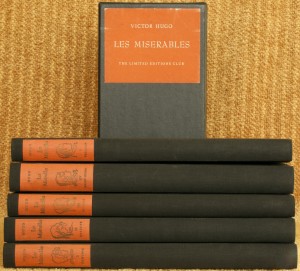

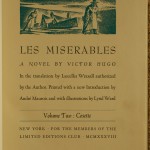

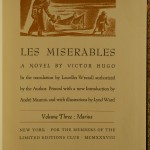

I have to say that reading Les Misérables in five volumes was a delight. It was so much less daunting reading the 1500+ pages in smaller, more manageable volumes of 250 to 350 pages each. The individual volumes are slim, not too large at 10 5/8 by 8 ½ inches, with a very readable size of type. When you leaf through one of the monstrous single paperback editions of Les Misérables, with it’s tiny type and dense pages, it’s no wonder readers are intimidated buy it. The Limited Editions Club (LEC) edition is 75 years old so it’s tough to complain too much but the black cloth really tends to show dirt and scuff marks.

I have to say that reading Les Misérables in five volumes was a delight. It was so much less daunting reading the 1500+ pages in smaller, more manageable volumes of 250 to 350 pages each. The individual volumes are slim, not too large at 10 5/8 by 8 ½ inches, with a very readable size of type. When you leaf through one of the monstrous single paperback editions of Les Misérables, with it’s tiny type and dense pages, it’s no wonder readers are intimidated buy it. The Limited Editions Club (LEC) edition is 75 years old so it’s tough to complain too much but the black cloth really tends to show dirt and scuff marks.

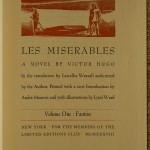

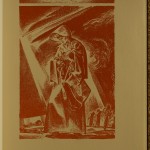

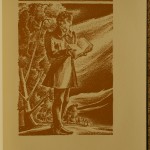

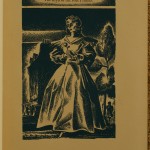

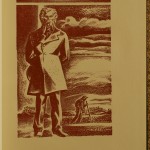

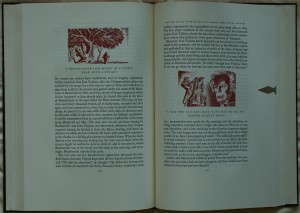

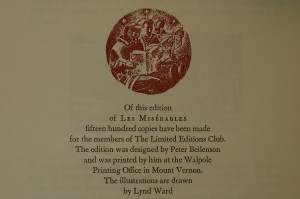

According to the colophon, the edition was designed by Peter Beilenson and was printed by him at the Walpole Printing Office in Mount Vernon. The illustrations are by the masterful Lynd Ward. I’m not sure how many he did but they are numerous. There are the full-page illustrations beginning the text of each volume, and then headpiece illustrations for each chapter as well as tailpiece illustrations in cases where the design of the page permitted. Some of the tailpieces were used multiple times but I believe each headpiece was unique. Each volume’s illustrations were done in a single color unique to that volume.

According to the colophon, the edition was designed by Peter Beilenson and was printed by him at the Walpole Printing Office in Mount Vernon. The illustrations are by the masterful Lynd Ward. I’m not sure how many he did but they are numerous. There are the full-page illustrations beginning the text of each volume, and then headpiece illustrations for each chapter as well as tailpiece illustrations in cases where the design of the page permitted. Some of the tailpieces were used multiple times but I believe each headpiece was unique. Each volume’s illustrations were done in a single color unique to that volume.

Hugo gives us so much to think about when we finish one of his novels. And it is important that he is still read, as for the most part the issues he wrote about are still with us. I must say that it is also so much easier to read him because you want to instead of it being a required assignment in a literature class. The pressures of time and grades could definitely cause one to be prejudiced against Hugo. It would indeed be a pity if we ever got to the point that most of us thought of the Broadway production when the words Les Misérables are spoken. The musical is wonderful; the book is extraordinary.

Hugo gives us so much to think about when we finish one of his novels. And it is important that he is still read, as for the most part the issues he wrote about are still with us. I must say that it is also so much easier to read him because you want to instead of it being a required assignment in a literature class. The pressures of time and grades could definitely cause one to be prejudiced against Hugo. It would indeed be a pity if we ever got to the point that most of us thought of the Broadway production when the words Les Misérables are spoken. The musical is wonderful; the book is extraordinary.

AVAILABILITY: This Limited Editions Club edition was published in 1938 in an edition of 1500. It is occasionally available through antiquarian and used booksellers but is scarce in fine condition. A two-volume version of this edition was published by the Heritage Press and is much easier and cheaper to find.

AVAILABILITY: This Limited Editions Club edition was published in 1938 in an edition of 1500. It is occasionally available through antiquarian and used booksellers but is scarce in fine condition. A two-volume version of this edition was published by the Heritage Press and is much easier and cheaper to find.

Note: I apologize for the overly yellow appearance of the paper in some of the photos. I’m still working on getting the white balance right for these types of shots. The paper is definitely creamy, more like in the colophon above. I did not have a copy of the LEC Monthly Letter to know what paper was used.

Note: I apologize for the overly yellow appearance of the paper in some of the photos. I’m still working on getting the white balance right for these types of shots. The paper is definitely creamy, more like in the colophon above. I did not have a copy of the LEC Monthly Letter to know what paper was used.